Interview:

Robert Bilott

When defence lawyer Robert Bilott agreed to help Earl Tennant prove that toxic chemicals from a DuPont landfill were killing the farmer’s cows and putting his family’s health at risk, he could not have known that he was prising open Pandora’s Box.

Tennant approached Bilott in 1998, convinced that the harrowing deaths being suffered by his cattle were the result of some substance leaching from the nearby landfill into the stream that ran through his land. He was right. That substance turned out to be perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and the scientific and legal battle to get DuPont to acknowledge the fact would last for two decades, eventually blowing up into a national public health scandal affecting every person in the US and consuming Bilott’s professional and personal life in the process.

Despite taking on DuPont – one of the biggest companies in the world – Bilott, through sheer grit, intelligence and tenacity, proved that the firm was doing more than dumping PFOA into a badly managed landfill – he uncovered it was discharging the toxic substance into the Ohio River and poisoning the drinking water of many towns and communities, causing a range of diseases including two types of cancer.

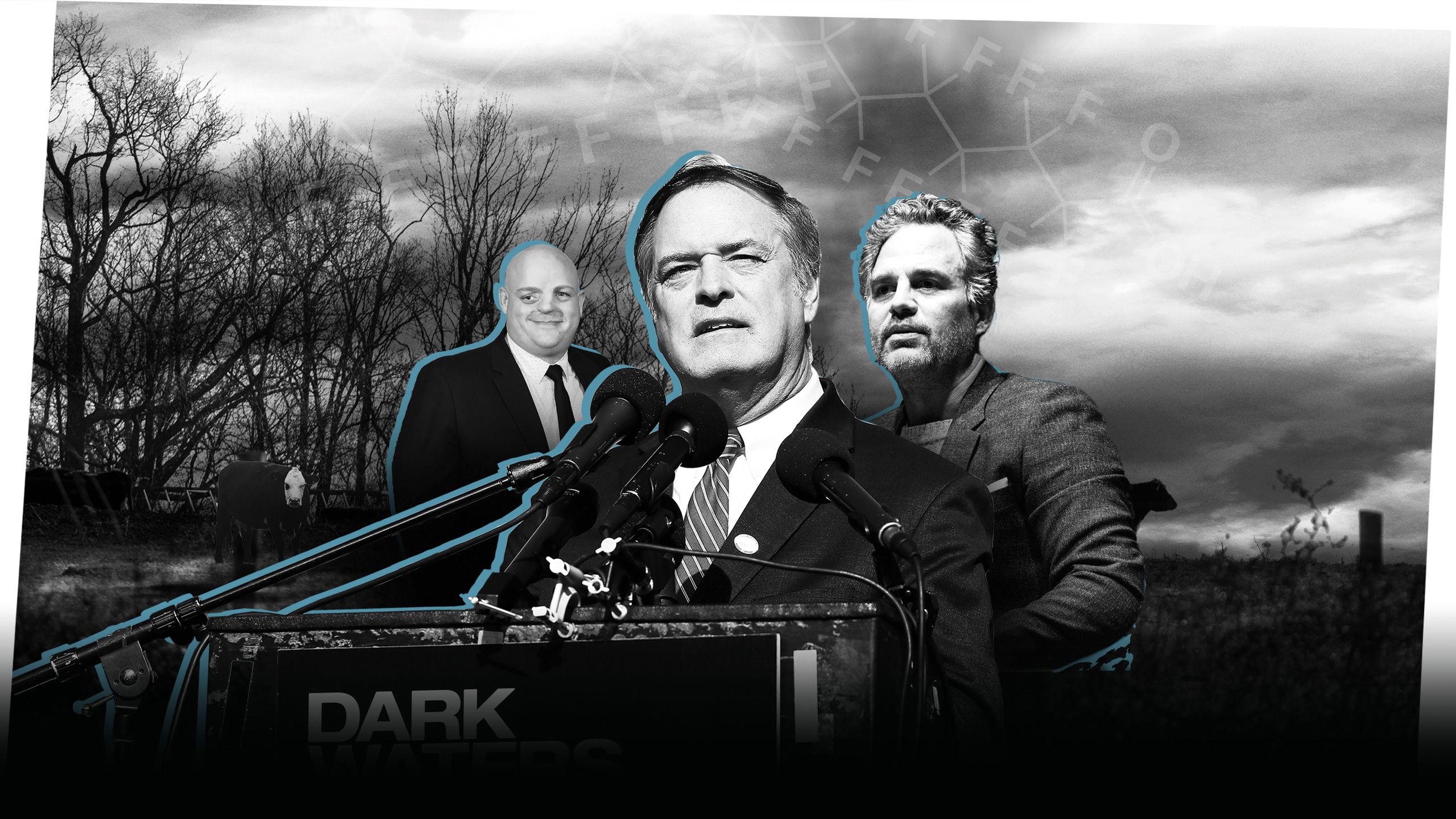

The titanic legal struggle gave rise to the 2019 Hollywood film Dark Waters starring Mark Ruffalo as Bilott, a book titled Exposure and a documentary called The Devil We Know.

It is now 23 years since Bilott first agreed to help Tennant fight DuPont. In that time he’s forced the chemicals giant to pay out around $753m (£540m) to one community along the Ohio River via litigation which spawned a huge number of new individual and class action cases across the United States as the nation faces up to the sobering fact that every American is likely to have per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) – a group of around 4,000 chemicals including PFOA and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) – in their blood.

CV: Robert Bilott

2020 Receives Taft’s Legacy Award

2019 Publishes Exposure: Poisoned water, corporate greed and one lawyer’s 20-year battle against DuPont

2019 Dark Waters hits the big screen

2018 The Devil We Know documentary is released

2017 Awarded the international Right Livelihood Award, known as the Alternative Nobel Prize for his work on PFOA

1990 Graduates from Ohio State University Moritz College of Law and joins Taft Stettinius & Hollister

Shifting the burden of proof

But this is just the warm up act, I find. We meet via Zoom, Bilott’s plain yellow background giving little away about the man at the centre of the storm.

“We’re seeking to bring a case on behalf of everyone in the United States who has PFAS in their blood,” he tells me. “It’s not to get money, it’s not to get damages for disease, but it’s to say: if you, the companies that are making those chemicals are going to sit back and say there’s not enough data to tell us whether they cause us harm, you companies ought to be paying for independent science to be done to confirm exactly what they’re doing to people.”

He is taking the same tack he used in his previous cases – but this time it is nationwide and it will take in the whole broader PFAS class of substances known as ‘forever chemicals’ because they are designed to never break down. “As you can imagine, all the companies moved to try to have it thrown out of court saying it was unprecedented, nobody’s ever done this, you can’t do this. But the judge denied those motions... and we recently filed papers to try to have it certified as a class action, which the companies are opposing, so that’s an ongoing battle.”

The Ohio River in Parkersburg was polluted with PFOA discharged by chemical maker DuPont. Photograph: The Washington Post/Getty Images

The bigger picture

In the meantime, Bilott is “working with helping states, water providers, people all over the country, trying to hold these companies responsible” for the “massive clean-up cost for impairing natural resources and all the drinking water supplies all over”.

This time, it is not just DuPont in the firing line. “When the US Environmental Protection Agency [EPA] finally came out with the very first drinking water guideline for PFOA and PFOS in the United States in May of 2016, the Department of Defence started putting together a list of all of the different locations across the US where firefighting foams [containing PFAS] had likely been used and went out and started testing,” says Bilott.

“So, from late 2016 to now, hundreds of locations have been tested in communities all over the United States... finding that this stuff’s in the water,” which has “triggered a whole new onslaught of lawsuits, because you have not only individuals and community members that are bringing claims saying our water is contaminated, but you now have public water providers, the people that are actually having to treat the water and incur millions of dollars to clean it up – they’re bringing lawsuits against the companies.”

Even states are bringing claims. “They’re saying: ‘You’ve contaminated the natural resources of the entire environment in our states – the fish, the soils, the water, the rivers, the streams’,” says Bilott.

Bilott is also investigating the impact of fire-fighting foams on water. Photograph: Mario Tama/Getty Images

It is clear the companies have woken up to the size of the problem. The week before we meet, DuPont and its spin-off company Chemours settled a legal dispute over how much money each company would pay into a $4bn fund earmarked for any future claims made against them relating to PFOA poisoning.

And in January, firefighting equipment firm Tyco agreed to a class action settlement of $17.5m for the people living near a firefighting training facility. Bilott says the company “will be agreeing to pay for property damage, for they’ve already committed that they will provide for clean water, but they’re also paying for damages for exposure to the chemicals. Even people that haven’t been diagnosed with a disease yet will get compensation for their exposure in the water. Plus, there will be compensation for people who have linked diseases”.

These results are good news but legal cases can drag on for years, acknowledges Bilott, saying the aim is that “forever chemicals don’t generate forever litigation”.

People are denied faster action because “a lot of laws and regulations... have not caught up to what we’re finding out about these chemicals”, he says. The US EPA has only just announced it will set a formal drinking water standard for PFOS and PFOA and “that’s still going to take several years”, he adds.

“These chemicals still aren’t declared hazardous under federal law so there are a lot of impediments to people being able to move forward with this process pretty quickly.”

There is some light on the horizon, with legislation to tackle the PFAS problem being proposed at the national level in the US for the first time, “so hopefully, we won’t have to keep litigating this until the end of time. Because right now, it’s being fought. It’s being fought in all of these courts, and there’s no end in sight”.

He wants the laws to “allow people not to have to spend their life in court in order to get clean water and to get compensated for damage”.

DuPont’s former Washington Works chemical plant in Parkersburg, West Virginia, is now operated by Chemours. Photograph: Maddie McGarvey/Getty Images

Easy data

Bilott’s book Exposure portrays the US EPA at best as weak for not tackling the pollution or dealing with DuPont in any meaningful way. He thinks that “to some degree... there is regulatory capture going on” and that DuPont’s close relationship with the EPA was a matter of concern.

“You’ve got a finite number of people at these agencies that are looking at this data. And when you’ve got companies that have unlimited resources, unlimited ability to focus on one or two chemicals in particular, and are able to walk into these agencies and say, ‘we’ve done the work for you here, we’ve drafted up all you need to know about this chemical – here it is’, it’s tempting to rely upon that information, particularly if you don’t know that you should be concerned or doubting that information.”

He says it has happened repeatedly. “It happens particularly in the smaller states that don’t have not only the resources, but don’t necessarily have people that can see how the data has been manipulated.”

Another thing that concerns the lawyer is the amount of time it is taking for the rest of the world to wake up to the dangers of PFAS.

“A lot of folks are not really fully grasping at this point... the true global scope of this. That this is not just a problem at a farm in West Virginia, or some one town along the Ohio River in the States, or even just one country... this is as global as you can get.”

The long struggle has taken its toll on the lawyer. There have been many moments of anxiety and even fear. In the film Dark Waters Ruffalo portrays Bilott in a scene in which it dawns on him that he could be in danger for knowing so much about DuPont’s dealings with PFOA – the firm knew the chemical was toxic and kept the fact hidden from the EPA and the public and continued to discharge it into the river. Following a tough meeting with the firm, Ruffalo is clearly worried as he walks through a quiet parking garage and pauses a while before turning the key in his car ignition.

Bilott remembers it well. “I was in Wilmington Delaware [taking the DuPont chief executive’s deposition], I was staying at the DuPont Hotel and I still vividly remember my parents on the phone the night before and they were asking me: why are you there and who else knows all of this? Who else has all the facts? And realising, frankly, it was probably just me. And at the end of that deposition, realising that the folks there weren’t too happy with me, having shown all this information to their CEO... all of those thoughts were swirling in my head as I walked back to that parking garage... so yes, it was concerning.”

HOW IS PFAS USED?

PFAS, a family of around 4,700 substances known as ‘forever chemicals’ because they are designed not to break down in the environment, is used by industries such as aerospace and defence, automotive, aviation, textiles, leather and apparel, construction and household products, oil production, mining, electronics, fire-fighting, food processing, and medical.

They are found in a wide range of consumer goods, including:

• Paper and card food packaging, such as takeaway containers, popcorn bags and pizza boxes

• Non-stick cookware

• Textiles, such as waterproof clothing and equipment, swimwear, carpets and mattresses

•Cleaning products, such as floor polish and car care products

• Cosmetics, including hair conditioner, foundation cream, sunscreen

• Electronics, such as smartphones

Personal toll

Bilott’s health has taken a battering too. A mysterious neurological disorder struck him in 2008. He suffered tremors and a palsy on his right side which turned into violent shaking convulsions up and down the right side of his body. The episodes would return at unexpected moments, leaving Bilott incapacitated. To this day, doctors are unable to explain why it is happening.

Bilott describes it as an “incredibly stressful” time, waiting for scientific results to come in that could make or break his case while at the same time “the entire US economy was collapsing”.

Then there was the “uncertainty of this case that was costing a lot of money, a lot of people are counting on me, and I’m getting calls about people getting sick, about people dying in that community, waiting for this information and that’s around the time these neurological issues developed”.

That case is over but the symptoms remain. “I’d like to be able to say they’re gone completely. I can’t. I don’t know if we’ll ever understand exactly what all it is, but it’s under control, at least I can say that. I’ve never figured out exactly what that was.”

Bilott appears well at least and it is clear his taste for the fight is undiminished.

“It’s pretty much what I do every day. It’s been incredibly encouraging to see... more people are recognising this issue or at least starting to recognise the scope of it and to see the change that can happen.”

He hopes it will encourage others to act. “One person standing up and speaking out even against odds that you think are insurmountable – one of the biggest companies in the world, taking on systems, scientific systems and regulatory processes that are all stacked against you – it can happen and things can change and hopefully people are inspired by that.”

Bilott’s come a long way since he was approached by Earl Tennant, who passed away in 2009. “I think he would be incredibly proud that we got this story out,” says Bilott. “That was one of his main concerns, he wanted to make sure that not only were his neighbours made aware and protected from this, but that everybody knew what happened here.

“I think that, knowing Earl though, and his family, they would be still not satisfied until we see that this stuff stops being emitted into the environment. We’re dealing with what’s out there in our environment and what’s there in people’s blood and we’re making sure that the people who did this to us are held responsible. We’ve been able to do that for at least the people along the Ohio River, and we’re still working on getting that done for everybody else.”

Health problems linked to PFAS include:

• High cholesterol

• Ulcerative colitis

• Thyroid disease

• Testicular cancer

• Kidney cancer

• Pregnancy-induced hypertension

• Miscarriage

• Endocrine disruption

• Reduced birthweight

• Reduced sperm quality

• Delayed puberty

• Early menopause

• Reduced immune response to tetanus vaccination

• PFAS contamination can also be passed on from mother to baby via the placenta and through breast milk.

There is less data relating to PFAS’s impacts on wildlife but studies have shown that chronic exposure could affect:

• The brain, reproductive system and hormonal system of polar bears

• The immune system and kidney and liver functions of bottlenose dolphins

• The immune system of sea otters

ENDS editorial produced by:

Editor Jamie Carpenter

Production editor Carolyn Avery

Art editor David Robinson

Group art director Tim Scott